Is Tech Causing Loneliness?

Remember when Saturday nights used to mean calling around to see what everyone was doing? Now we just scroll through Instagram stories, watching other people’s nights unfold from the comfort of our couch. We know exactly where our friends went, what they ate, who they were with – but somehow we feel more disconnected than ever.

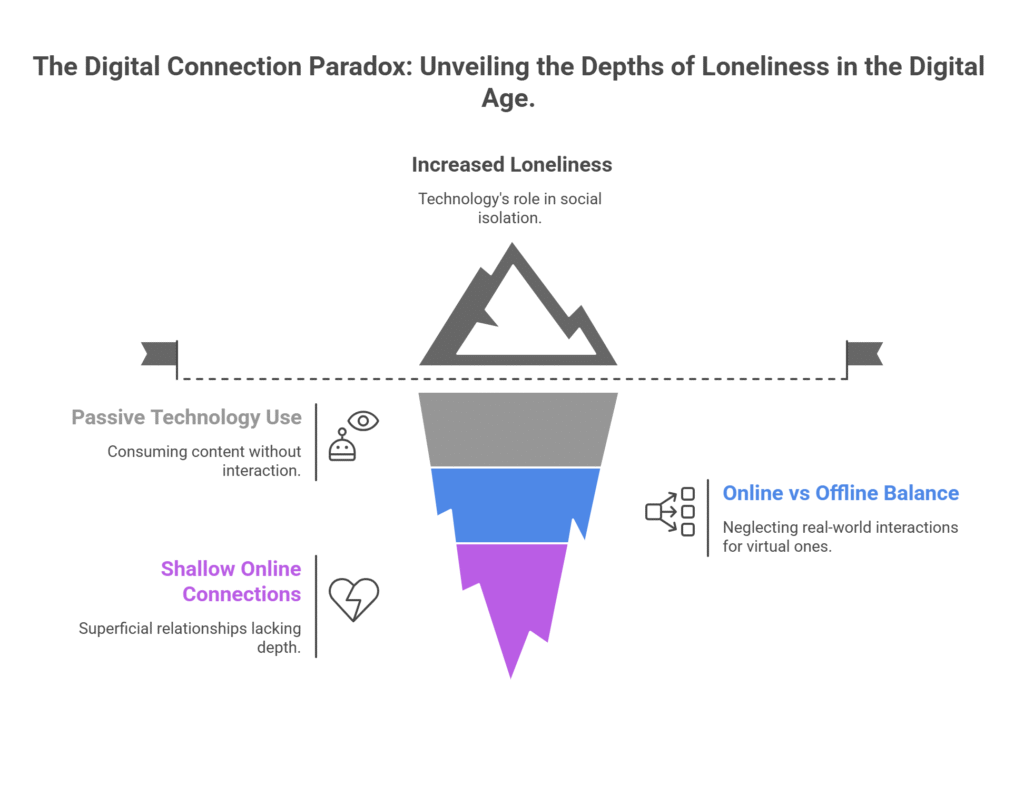

It’s kind of ironic when you think about it. We’re living in the most connected era in human history, yet the U.S. Surgeon General has declared a loneliness epidemic affecting nearly half of all American adults. We have thousands of followers, hundreds of contacts in our phones, and instant access to anyone, anywhere, anytime. So why do so many of us feel profoundly alone?

The answer isn’t as simple as “smartphones bad, real life good” – though that’s certainly part of the conversation happening everywhere from dinner tables to medical journals. The relationship between technology and loneliness is messier than most people want to admit. Sometimes our devices bring us closer together. Sometimes they drive us further apart. The trick is figuring out which is which, and more importantly, what we can do about it.

Understanding the Scale of Modern Loneliness

Let’s start with some numbers that might surprise you. According to recent surveys, about 47% of Americans report feeling lonely on a regular basis. That’s nearly one in two people walking around feeling disconnected from others. Among young adults aged 18-25, that number jumps even higher – they actually report more loneliness than seniors, despite being surrounded by digital social networks.

But here’s where it gets interesting: loneliness has been steadily increasing since the 1970s, long before social media existed. Robert Putnam documented this trend in his famous book “Bowling Alone,” showing how Americans were becoming less connected to their communities, neighbors, and even family members decades before the first Facebook post.

The pandemic certainly accelerated things. At the height of lockdowns, 25% of Americans reported feeling lonely “a lot of the day.” That number has dropped to about 17% as things reopened, but we’re still talking about 44 million people feeling isolated. To put that in perspective, that’s more than the entire population of California.

What makes these statistics particularly concerning is that chronic loneliness isn’t just emotionally painful – it’s physically dangerous. Research suggests that prolonged social isolation increases mortality risk by about 50%, comparable to smoking 15 cigarettes a day. It’s linked to increased rates of heart disease, stroke, diabetes, cognitive decline, and even Alzheimer’s disease.

The health implications have gotten so serious that several countries, including the UK, have appointed Ministers of Loneliness to address what they’re calling a public health crisis. Japan has a similar position because of their epidemic of social withdrawal, particularly among young men.

The Social Media Paradox

Here’s where things get complicated. Social media was supposed to solve loneliness by connecting us with more people more often. In some ways, it has. During the pandemic, video calls and social platforms helped maintain relationships that would have otherwise withered. Grandparents learned to FaceTime their grandchildren. Long-distance friendships survived through group chats and shared memes.

Research shows that when people use social media to maintain existing relationships or find communities around shared interests, it can actually reduce loneliness. The key word there is “existing.” Platforms work well as supplements to real-world relationships, not replacements for them.

The problem comes when we start using social media as our primary form of social interaction. Multiple studies have found that people who spend more than two hours a day on social platforms report significantly higher rates of perceived social isolation. That’s because passive consumption – scrolling through feeds, watching others’ highlight reels – doesn’t satisfy our need for genuine human interaction.

There’s also the comparison trap. When you’re home alone on a Friday night scrolling through everyone else’s party photos, you’re not just missing out on social interaction – you’re actively reinforcing the narrative that everyone else is having more fun than you are. Never mind that half those people probably went home early and felt just as lonely as you do.

Weirdly enough, people who use social media specifically to maintain relationships report feeling lonelier than those who use it more casually. It’s like the more we try to digitally manufacture the connections we’re missing, the more aware we become of what’s lacking.

The Attention Economy’s Role in Isolation

Let’s talk about something most people don’t consider: social media platforms make money by keeping us scrolling, not by making us happy. The longer you stay on the app, the more ads you see. The more emotionally engaged you get, the more likely you are to keep coming back.

This creates what researchers call “problematic internet use” – compulsive checking that interferes with real-world activities and relationships. You’ve probably experienced this yourself: choosing to scroll through TikTok instead of calling a friend, or feeling anxious when you can’t check your phone for a few hours.

The algorithms are designed to show us content that provokes strong emotional reactions, whether positive or negative. Outrage keeps us engaged just as much as joy does. But constantly consuming emotionally charged content – even positive stuff – can leave us feeling drained and less interested in the slower, more subtle rewards of face-to-face interaction.

Think about it: real conversations require patience, attention, the ability to sit with awkward silences. Social media trains us to expect constant stimulation and immediate gratification. No wonder so many people, especially younger adults, report feeling anxious about making phone calls or having unstructured social time.

There’s also what psychologists call “continuous partial attention” – the habit of never being fully present in any one moment because we’re always monitoring our devices. You can’t build deep relationships when half your attention is always elsewhere.

The Decline of Third Places

Before we blame technology entirely, we need to look at what else has changed in how we structure social life. Sociologist Ray Oldenburg coined the term “third places” – locations that aren’t home or work where people naturally gather and interact. Think coffee shops, libraries, community centers, neighborhood bars, places of worship.

These third places have been disappearing for decades. Suburban sprawl made everything car-dependent. Economic pressures forced many small businesses to close. Community organizations lost membership. Even when these spaces exist, we often experience them differently – buried in our phones instead of talking to strangers.

The result is that many people’s social lives have become entirely intentional and planned. Instead of running into neighbors or striking up conversations with regulars at local hangouts, we have to actively schedule social time. That’s exhausting and it doesn’t replicate the natural, low-stakes social interactions that help combat loneliness.

Work relationships have changed too. Remote work has benefits, but it’s eliminated the casual conversations that used to happen at the coffee machine or during lunch breaks. Many people report feeling professionally isolated, especially younger workers who never experienced traditional office culture.

Even when people do gather in person, technology often intrudes. How many times have you been at dinner with friends where everyone was periodically checking their phones? We’re physically present but psychologically scattered.

The Quality vs Quantity Question

One thing researchers consistently find is that the number of social media friends or followers has almost no correlation with reported loneliness levels. What matters is the quality of relationships, not the quantity. You can have 1,000 Instagram followers and still feel completely alone.

This creates what some researchers call the “loneliness in a crowd” phenomenon. Young adults, despite being more digitally connected than any generation in history, report the highest levels of loneliness. They have access to more people than ever before, but fewer deep, meaningful relationships.

Part of this might be developmental. Learning to form close relationships is a skill that requires practice, and if you spend your formative years primarily interacting through screens, you might not develop the social skills needed for intimate friendships. Some young adults report feeling anxious about phone calls or face-to-face conversations because they’re so used to the asynchronous, edited nature of digital communication.

There’s also the issue of vulnerability. Real intimacy requires emotional risk – sharing things about yourself that someone might judge or reject. Social media allows us to curate our presentation and control how others see us. But that same control makes it harder to be genuinely known by others.

Many people report having lots of “weak ties” – people they follow online or occasionally chat with – but few “strong ties” – people they can call at 3 AM when they’re having a crisis. Strong ties are what protect against loneliness, but they require time, emotional labor, and mutual vulnerability that’s hard to develop through screens.

Age-Related Digital Divides

The relationship between technology and loneliness looks different across age groups. Older adults were initially the most resistant to digital adoption, but the pandemic forced many to get online to maintain social contacts. For seniors who successfully learned to use video calling and social media, technology has been largely beneficial for reducing isolation.

But older adults face unique challenges. Physical limitations can make using devices difficult. Many lack the technical support needed to troubleshoot problems. Age-related cognitive changes can make learning new interfaces frustrating. The result is that technology intended to help combat senior loneliness sometimes creates additional barriers.

On the flip side, digital natives – people who grew up with smartphones and social media – face different challenges. They’re comfortable with the technology but may not have developed strong skills for in-person interaction. Some report feeling more confident communicating through text than face-to-face conversation.

Middle-aged adults often struggle with the transition to digital communication in relationships that formed before social media existed. They may feel obligated to maintain online presences they don’t enjoy, or frustrated by friends who prefer texting to phone calls.

The Remote Work Revolution’s Social Costs

The shift to remote work, accelerated by the pandemic, has created new forms of professional loneliness. While many people appreciate the flexibility of working from home, they also report missing the informal social interactions that happen in shared workspaces.

This is more than just missing office happy hours. Work relationships often serve as important sources of social support and identity. When those relationships become purely transactional – focused only on getting tasks done rather than building personal rapport – people can feel isolated even when they’re constantly in virtual meetings.

The boundaries between work and personal life have also blurred in ways that can increase loneliness. When your bedroom is your office and your laptop is your primary social interface, it becomes harder to create the psychological separation needed for different types of relationships.

Young professionals seem especially affected. Early career networking, mentorship, and workplace friendship formation all happen differently (or not at all) in remote environments. Many recent graduates report feeling professionally adrift, unsure how to build the relationships that traditionally helped people establish their careers and social identities.

Digital Communication’s Emotional Limitations

Let’s be honest about something most people don’t want to admit: digital communication is emotionally impoverished compared to in-person interaction. We lose tone of voice, body language, facial expressions, and the subtle cues that help us understand each other’s emotional states.

This creates what researchers call “communication dissatisfaction” – the feeling that digital interactions aren’t quite meeting our social needs, even when we can’t articulate why. Text messages can be misinterpreted. Video calls feel slightly off because of audio delays and the uncanny valley effect of looking at screens instead of eyes.

But we adapt to these limitations in ways that might be making loneliness worse. We start to prefer the edited, controlled nature of digital communication because it feels safer. We avoid phone calls because they feel too intense or unpredictable. We substitute emoji for emotional expression because it’s easier than articulating complex feelings.

The result is that our communication becomes increasingly surface-level, even in close relationships. We share information and logistics but less emotional vulnerability. Over time, this can make relationships feel hollow, even when they’re technically being maintained.

Some people report feeling “digitally lonely” – connected to others through technology but starved for the kind of physical presence and unmediated interaction that creates genuine intimacy. You can text someone all day and still feel like you don’t really know them.

The Paradox of Choice in Digital Relationships

Dating apps illustrate another way technology might be contributing to loneliness. These platforms promise access to more potential partners than you could ever meet organically, but many users report feeling overwhelmed by choices and struggling to form meaningful connections.

The “shopping” mentality that apps encourage – swiping through potential matches like you’re browsing products – can make it harder to invest emotionally in any one person. Why work through relationship challenges when there are hundreds of other options available?

This choice overload extends to friendships too. Social media keeps us connected to acquaintances from every period of our lives, but this breadth can come at the expense of depth. Instead of deepening relationships with people in our current circumstances, we spread our social energy across dozens of casual connections.

There’s also what psychologists call “FOBO” – fear of better options. When you can see what everyone else is doing all the time, it becomes harder to commit fully to the people and activities right in front of you. Always having one eye on potentially better social options can prevent the kind of sustained attention that builds strong relationships.

Technology as Solution vs. Technology as Problem

Here’s the thing that makes this whole conversation frustrating: technology isn’t inherently good or bad for loneliness. It’s a tool, and like any tool, its impact depends on how we use it.

Video calls helped isolated seniors stay connected to family during the pandemic. Online communities provide support for people dealing with rare medical conditions or niche interests that they can’t find locally. Social media helps maintain long-distance friendships that would otherwise fade.

But the same technologies can also enable avoidance of in-person interaction, create addictive usage patterns, and foster unhealthy social comparisons. The difference often comes down to whether we’re using technology intentionally to support our social goals or mindlessly consuming it as entertainment.

Research suggests that “active” social media use – commenting, messaging, sharing personal updates – is associated with better well-being than “passive” use – scrolling through feeds without engaging. Similarly, using technology to coordinate in-person activities tends to reduce loneliness, while using it as a substitute for face-to-face interaction tends to increase it.

The key insight from loneliness research is that humans need multiple types of social connection: intimate relationships with family and close friends, casual acquaintanceships with neighbors and coworkers, and a sense of belonging to larger communities. Technology can support all of these, but it works best when it supplements rather than replaces in-person interaction.

Individual Strategies for Connection

So what can individuals do about this? First, recognize that loneliness is normal and treatable, not a personal failing. The shame around admitting loneliness often makes it worse by preventing people from taking action to address it.

Start by auditing your technology use. How much time do you spend passively consuming social media versus actively connecting with people you care about? Are your devices helping you maintain relationships or distracting you from them? Simple changes like turning off notifications or setting specific times for checking social media can create more space for in-person interaction.

Focus on strengthening existing relationships rather than constantly seeking new ones. Call someone instead of texting. Suggest meeting in person instead of having another video chat. Put your phone away during social time and practice being fully present.

Look for opportunities to create “weak tie” interactions in your daily life. Chat with neighbors, make small talk with cashiers, attend community events. These brief social exchanges don’t replace close friendships, but they contribute to a sense of social connection and community belonging.

Consider the role of physical spaces in your social life. Do you have places where you regularly see the same people? If not, try joining a gym, volunteering somewhere, taking a class, or becoming a regular at a local coffee shop. Repeated exposure is how many friendships naturally develop.

Quick Takeaways

• The loneliness epidemic predates social media by decades, with social isolation increasing steadily since the 1970s due to broader cultural and structural changes

• Technology’s impact on loneliness depends on usage patterns – active engagement that supports existing relationships tends to help, while passive consumption often increases isolation

• Young adults report higher loneliness rates than seniors despite being more digitally connected, suggesting quantity of online connections doesn’t equal quality of relationships

• The decline of “third places” like community centers and local gathering spots has eliminated natural opportunities for casual social interaction that historically protected against isolation

• Remote work and digital communication, while offering flexibility, can create professional loneliness and reduce the informal social contacts that traditionally happened in shared workspaces

• Digital communication lacks the emotional richness of in-person interaction, leading to “communication dissatisfaction” even in maintained relationships

• The most effective approaches to reducing loneliness combine technology use with intentional in-person activities and community engagement rather than avoiding digital tools entirely

Reframing Our Relationship with Digital Connection

Look, we’re not going back to a pre-digital world, and honestly, most of us wouldn’t want to. Technology has given us amazing tools for maintaining relationships across distance and time. The question isn’t whether to use these tools, but how to use them wisely.

The loneliness epidemic isn’t really about technology – it’s about how we’ve structured modern life in ways that make meaningful connection harder to achieve and maintain. Yes, social media and smartphones play a role, but so do suburban design, economic inequality, work culture changes, and the breakdown of traditional community institutions.

Blaming technology for loneliness is appealing because it suggests a simple solution: just put down your phone and magically feel connected again. But the reality is more complicated. Some of the loneliest people I know barely use social media, while others have built genuine communities online that sustain them through difficult times.

What seems to matter most is intentionality. Are you using technology in service of your social goals, or is it using you? Are your digital habits bringing you closer to the people you care about, or pulling you away from them? These aren’t one-time questions – they require ongoing reflection as both technology and our life circumstances change.

The good news is that humans are incredibly adaptable social creatures. We figured out how to maintain relationships through letters, telephone calls, and early internet forums. We’ll figure out how to do it with whatever comes next too. But it requires conscious effort to ensure that our tools serve our fundamental need for connection rather than undermining it.

Maybe the real lesson of the loneliness epidemic is that connection has always required work. The difference now is that we have to be more deliberate about creating the conditions for intimacy and community. That’s not necessarily a bad thing – it just means we can’t take relationships for granted the way previous generations could.

The technology isn’t going anywhere. The loneliness doesn’t have to stay either.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is social media really making people lonelier, or is that just a moral panic? Research shows a complex relationship – passive social media use (scrolling feeds) is linked to increased loneliness, while active use (commenting, messaging friends) can reduce it. The key is how you use these platforms, not whether you use them at all.

Why do young people report more loneliness than older adults despite being more connected digitally? Digital connections don’t automatically translate to meaningful relationships. Young adults may have hundreds of online acquaintances but fewer close friendships. They’re also still learning relationship skills that previous generations developed through more in-person interaction.

Can online relationships be as meaningful as in-person ones? Online relationships can be deeply meaningful, especially when they supplement rather than replace face-to-face interaction. However, digital communication lacks some emotional richness, so purely online relationships may feel less satisfying over time.

How much social media use is too much when it comes to loneliness? Studies suggest that more than two hours daily of social media use is associated with increased feelings of social isolation. But quality matters more than quantity – two hours of meaningful interaction with friends is different from two hours of passive scrolling.

Did the pandemic permanently change how lonely people feel? Loneliness spiked during lockdowns but has decreased as restrictions lifted. However, some pandemic-era changes like increased remote work and reduced casual social interaction may have lasting effects on social connection patterns.

What’s the difference between being alone and being lonely? Being alone is a circumstance – you’re physically by yourself. Being lonely is an emotional state – feeling disconnected from others even when surrounded by people. You can be alone without being lonely, and lonely without being alone.

Are there any benefits to moderate loneliness? Brief periods of loneliness can motivate people to seek social connection and reflect on their relationships. However, chronic loneliness is harmful to both mental and physical health and should be addressed through social connection or professional support.